8. The Theory of Music

Section 117.12 Music, Grade 3. ...The student is expected to: ..use music terminology in explaining sound, music, music notation, musical instruments and voices, and musical performances; and identify music forms presented aurally such as AB, ABA, and rondo.”

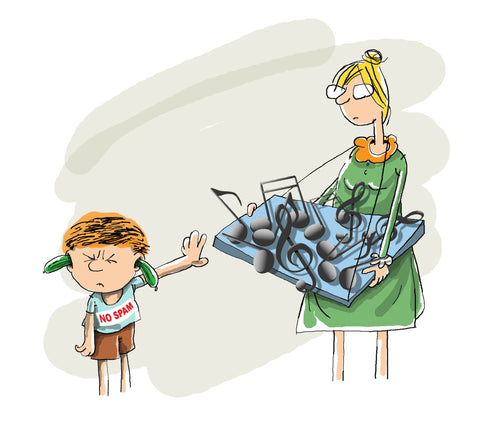

We don’t like spam, and wave away any useless piece of information. This is especially true when it is information that we didn’t even ask for. Above the door into our conscious perception hangs a sign saying “No solicitation!” However, we educators tend to forget about that. We become aggressive spammers, though we don’t want to admit it. We tie the theory of music around the student’s neck, and don’t even bother to make it more desirable to the student.

It’s obvious that our calling is most noble. They say that the student will undoubtedly need theoretical understanding in the future! But you see, the child’s perception doesn’t share this view. It only wants what is needed at the moment. You don’t believe me?

Imagine that you are about to go on a long and complicated trip. You are of course waiting for the day of the trip to purchase a map. But the guide gathers everybody a week in advance instead and spends an hour reading a lecture about the route you need to take. After that, he demands that you commit the directions to memory! I have no doubts that you won’t remember much. Your attention is a fickle thing – after all, the lecture isn’t of any use to you at the moment. You aren’t going anywhere anytime soon, are confused and disappointed with the guide, and besides, it’s lunchtime, and your stomach’s starting to rumble. Later on, when you will get lost, you’ll naturally think of that cursed guide and wonder why he didn’t simply just give you a map!

This is exactly how theory is taught – teachers explain the route during music lessons. Not taking a single step on the path (as children only learn to play by ‘composing and improvising’), they keep the map out of the student’s hands. Instead they read long, imaginative lectures, and test the children by playing short recordings that they are asked to identify. The perception has no idea why it needs this information yet! It resists. This makes it necessary to stuff the lessons with as much information as possible, which is what occupies the majority of teachers’ time.

Isn’t it about time to quit battling with our students? It’s a lot easier to make arrangements so that the student himself will want to find out what the Treble Clef is, and what differentiates it from the Bass Clef. This isn’t hard at all. All you have to do is ‘fill the pool with water’ and teach your pupil to swim. In other words, begin with the development of skills. The most important skills are reading notes from sheet music and singing by notes. Here, in reality, with the growth of possibility, the perception won’t only ask for more information, but will pray for it, will catch at every word as if it were manna falling from heaven!

We have been taught that knowledge of the terminology is the very personification of musical literacy. It seems that this is why we love theory so much. The ability to pronounce smart words on the spot is much more important to some than the ability to sit with an instrument and play something worthwhile. But let’s face the facts: If a person can’t play a simple piece from sheet music, is it really important for him to know what Andate sostenuto is?

I am reminded of my first flight to the U.S. I came to America as a “literate” person. I had mulled over tons of books about English grammar, and even knew the different types of verbs and the correct structures of sentences. Yet, when I very properly asked one lady, “What time is it?” her answer confused me. I didn’t understand a single word in the stream that came forth from her mouth. It was an important lesson: Knowledge of the rules isn’t the same as the ability to talk and understand! It is important to properly communicate in the language of music and to understand it, not delight in familiar names for abstract musical terms.