Recreating the musical alphabet and text formats according to the ideas of Guido of Arezzo using modern technology.

It is known that the alphabet and various text formats saved people from total illiteracy. Until a picture was placed near the letter, phonetically explaining how it sounds, beginners had to memorize abstract signs and then “overlay” the memorized audio onto the printed version from the Bible and the Psalter.

Before the widespread introduction of the ABC’s with pictures, until the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century, people from different countries of the world were illiterate. The alphabet with pictures turned out to be a circumvented, but insufficient, condition for a revolutionary breakthrough in solving total illiteracy.

Text formats, when the letter size and the number of lines on a page increase or decrease accordingly to the student’s visual perception, were a milestone in the development of universal literacy of the population of any age. Today, many children go to school already knowing how to read!

In musical pedagogy, universal literacy is still a huge problem that negates all the efforts of professionals. Music lessons in public schools do not give reading skills to all children. In music classes with professional tutors, progress is also small: sometimes even graduates perform pieces by memorizing the movements of the hands of the teacher and are not able to read the musical text themselves. The situation echoes the total illiteracy of the population BEFORE creating the ABC’s and transitional text formats.

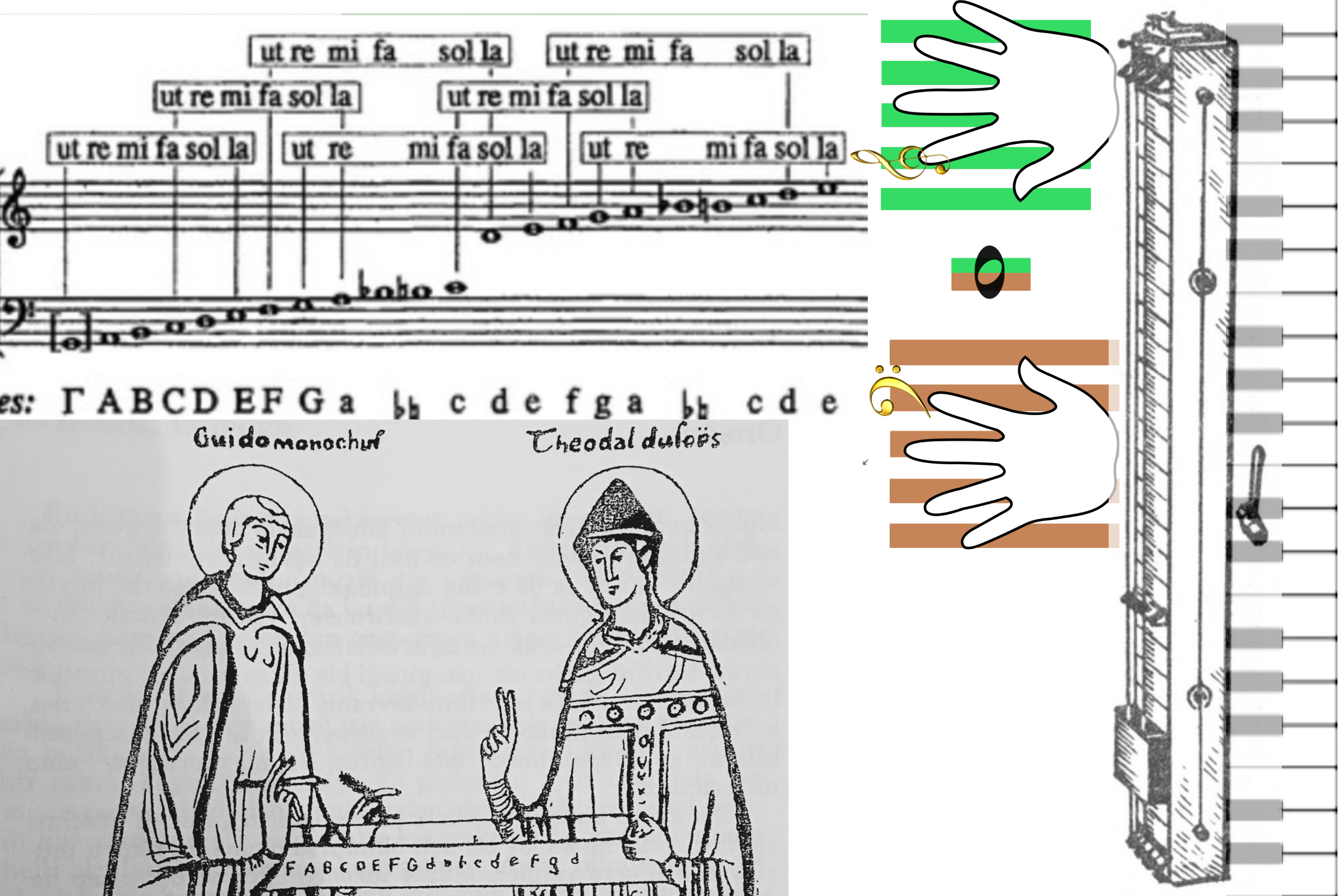

Meanwhile, a basic approach to reading notes was already laid down 1000 years ago by Guido of Arezzo. The development of writing music, as well as the development of musical instruments, is a direct clue to creating a musical alphabet and various text formats that can be adapted to the visual perception of beginners.

1. Lines and spaces are the key to reading a multi-linear musical text. We know that it was Guido who placed the notes on the lines and in the spaces between them. However, this fundamental part of writing music is truly underestimated by modern music education. The whole essence of reading musical notes lies in a person’s ability to navigate among lines and spaces.

Modern and poorly working musical pedagogy comes from musical notes and keys with no regards to their placement on the staff (learning octaves, locating the keys next to 2 and 3 black keys, the study of each note separately by name, even by color coding each note). In fact, organizing notes on 5 + 5 lines is more efficient.

2. Sound and sign are part of a single whole. If in the ABC’s A, there is “apple,” which helps to “stretch” the sound with the help of a picture, then in music, this role is played by solmization. Guido of Arezzo created this system and combined the solfeggio syllables with the precise sound of the corresponding vibration of the monochord. All this was also connected with the student's ability to see the sounding syllable on the lines and between the lines of the music score.

However, with the development of written polyphony, a clear visual connection between the pitch of the notes and their symbols was broken.

Turning the stave with the keys up helps to restore the visual unity of each note with the key, which reunites the sound and the sign and helps each student to develop both visual and auditory reading of the text, playing both treble and bass simultaneously.

Guido connected the lines with “white keys.” In his era, before the creation of the keys, there was only one prototype of the black key--B flat (to avoid the triton between fa and ti). The study of musical writing with the primary involvement of black keys violates Guido's plan and leads students away from direct interaction with the sign and sound.

3. Creation of the Grand Staff as the most convenient system for recording multi-linear sheet music. In the days of Guido, the keys “floated” according to the singing range of the choir singers. This is what has led modern musical pedagogy to a standstill.

However, the Grand Staff range was already laid down by the great Benedictine and was described by him in the treatise “Micrologus”: from the G of the small Octave to D of the second “and higher.”

Lines are “human fingers.”

The left hand, bass key from the thumb to the little finger: A-F-D-B-G.

The right hand is the treble clef from the thumb: E-G-B-D-F.

Middle C is a 0 (zero) in such a “thermometer.” Lines should be counted from 0 (zero) symmetrically. Bass and treble clefs are part of a single whole. Index fingers indicate the location of the keys G and F.

This forces a radical revision of music theory textbooks, in which the keys are studied separately and the bass lines are counted from the bottom up.

4. The visual focus of a person physiologically works pointwise. First, the child learns to focus on one object then learns to read among the lines or to move the eye’s focus from object to object. Guido's musical notation was initially single lined.

However, with the development of written polyphony, the musical text turned into a “chessboard” for unprepared visual perception. It is advisable to return one line to the elementary education, as Guido had planned, but without cutting the stave to one key. It is enough to use the vertical line from button up (bass to treble) per real time unit.

5. Note-sound as a process. It is known that music is a timing language. Each duration has a beginning, development and completion. In Guido's time, the duration of each note was easily conveyed by the text of the prayer.

Modern pedagogy is deprived of this resource. In this regard, one of the most important means for transmitting the procedural nature of a musical text is interactive computer graphics.

The beginning, development, and completion of each duration is easy to convey with the interactive animation of a blossoming flower, from the bud to the full opening of the petals. In this sense, modern technology is an indispensable tool for communicating in real time with musical texts.

6. Text formats from alphabetical to traditional. Modern ineffective musical pedagogy is trying to adjust the student's visual perception to an inflexible format of musical text, which largely makes music notation an unfriendly interface and scares away a huge amount of the population from musical literacy.

Modern computer technologies easily transform a musical text from alphabetical to traditional and help any beginner choose the format that is most convenient for perception and move from simple to complex as easily and simply as from a picture book to a chapter book and novel.

All these most important facts (which have been missed by modern pedagogy) have been implemented by a flexible text submission system called Soft Way to Mozart.

This program is a development of the alphabetical approach in communicating with musical text, conceived by Guido of Arezzo 1000 years ago. This approach with its software is a breakthrough in music education.

Testing in 60 countries with students from 2 years of age, as well as special-needs children leaves no doubt: this is the way that will help spread musical literacy throughout the general population, which will bring the development of musical language to a new, more progressive level.

Hellene Hiner, Houston, TX USA

February, 1 2020